Pancreatitis

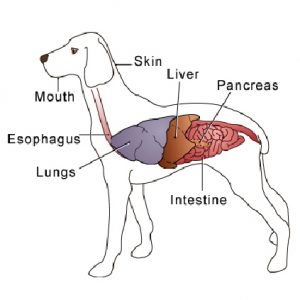

The Pancreas is a V-shaped organ that is located behind the stomach and the first section of the small intestine, the duodenum. It has two main functions – to aid in the metabolism of sugar in the body through the production of insulin, and is necessary for the digestion of nutrients by producing pancreatic enzymes. Different mechanisms produce different enzymes – for example, eating fat stimulates a different enzyme than eating protein.

Pancreatitis occurs when the pancreas becomes inflamed (tender and swollen).

Pancreatitis can be caused by many things:

Certain medications (especially the combination of potassium bromide and phenobarbital, used to control epilepsy), as well as some anti-cancer drugs and some antibiotics. Many other medications have been linked to pancreatitis, including certain antibiotics, diuretics, other anti-epileptic drugs, hormones, long-acting antacids and aspirin.

Corticosteroids, such as prednisone, are believed to cause pancreatitis. However, dogs with immune-mediated pancreatitis may respond well to corticosteroids, which suppress the immune system.

Metabolic disorders, including hyperlipidemia (high amounts of lipid in the blood) and hypercalcemia (high amounts of calcium in the blood).

Hormonal diseases such as Cushing’s disease (hyperadrenocorticism), hypothyroidism, and diabetes mellitus.

Obese and overweight dogs appear to be more at risk.

Genetics may play a role (especially Schnauzers and Yorkshire Terriers).

Nutrition – dogs with diets high in fat, dogs who are fed table scraps, or dogs who steal seem to have a higher incidence. A fatty meal can trigger it in middle-aged, overweight and relatively inactive dogs.

Low-protein diets can predispose dogs to pancreatitis, especially when combined with high fat intake. Some prescription diets, such as those prescribed to dissolve struvite bladder stones, to prevent calcium oxalate, urate, or cysteine stones, and to treat kidney disease, may be a concern.

Abdominal surgery, trauma to the abdomen (e.g. being hit by a car), shock or other conditions that could affect the blood flow to the pancreas. Surgery has also been linked to pancreatitis, probably due to low blood pressure or low blood volume caused by anaesthesia.

Toxins, particularly some organophosphates (insecticides used in some flea control products), may lead to canine pancreatitis.

Other theoretical causes include bacterial or viral infections, vaccinations, obstruction of the pancreatic duct, reflux of intestinal contents up the pancreatic duct, impaired blood supply to the pancreas, bloat and a tumour in the pancreas.

Previous pancreatitis

In most cases, the cause is never found.

They symptoms of pancreatitis may range from mild to very severe, and are similar to other diseases. They may include a very painful abdomen, abdominal distention, lack of appetite, depression, dehydration, a hunched up posture, a praying position, vomiting and possibly diarrhoea. Fever may also be present. In the case of a severe disease, symptoms can include arrhythmias, sepsis (body-wide infection), difficulty breathing, and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), which results in multiple haemorrhages. If the inflammation is severe, organs surrounding the pancreas can be ‘autodigested’ by pancreatic enzymes released from the damaged pancreas and become permanently damaged.

Chronic pancreatitis is a low-grade inflammation of the pancreas. Symptoms such as vomiting and discomfort after eating may occur intermittently, sometimes accompanied by depression, loss of appetite and weight loss. Signs may even be as subtle as a dog not wanting to play normally, being a picky eater, or skipping a meal from time to time.

Pancreatitis can be diagnosed by first ruling out other causes of the symptoms, taking a history of the dog and taking a complete blood count to look for levels of the two pancreatic enzymes amylase and lipase (although an absence of raised levels does not rule out pancreatitis). Chemistry panel, urinalysis, the canine pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity test, X-rays and ultrasound can also be useful in making a diagnosis. An ultrasound can also reveal some potential complications associated with pancreatitis, such as a blockage of the bile duct from the liver as it runs through the pancreas.

The goals of pancreatitis treatment are to:

Correct dehydration and electrolyte imbalances, either subcutaneously or intravenously (depending on the severity of the condition)

Provide pain relief

Control vomiting – medications are often given to decrease the amount of vomiting, and in severe cases food, water and oral medications can be withheld for 24 hours. The dog generally needs to be fed small meals of a bland, easily digestible, low-fat food.

Provide nutritional support – it is critical to ensure that the dog received sufficient appropriate nutrition whilst the condition is brought under control. In the short term, the goal of nutrition is to stop leaky gut syndrome, rather than to supply total caloric needs.

Prevent complications

Surgery may be necessary, particularly if the dog’s pancreas is abscessed or the pancreatic duct is blocked.

If pancreatitis was caused by a medication, that medication should be stopped. If caused by a toxin, infection or other condition, then the appropriate therapy for the underlying condition should also be started.

If the pancreatitis was mild and the dog only had one episode then the chances of recovery are good. Some animals develop chronic pancreatitis, which can lead to diabetes mellitus and/or pancreatic insufficiency (where the nutrients in food are passed out of the body undigested). To treat pancreatic insufficiency, digestive enzymes are replaced via a product processed from the pancreases of hogs and cattle.

Without oral nutrition the intestines starve, even if nutrition is provided to the rest of the body through IVs. This is because the intestines receive their nutrition only from what passes through them. Because most dogs with pancreatitis are unwilling to eat, a liquid diet may be fed via a tube placed through the nose, oesophagus or stomach. Dogs may tolerate nasoesophageal feeding even when vomiting persists.

It is possible that the addition of omega-3 fatty acids (using fish body oil, not cod liver oil), pancreatic enzymes, medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs - a form of fat that does not require pancreatic enzymes for digestion), and the amino acid l-glutamine to the liquid nutrition may help with recovery. Virgin coconut oil is an excellent source of MCTs. Probiotics are not recommended for dogs with acute pancreatitis, but they can be given once the dog has recovered.

The herbs dandelion, burdock root, and Oregon grape can help improve digestion and reduce pancreatic stress, by gently increasing bile and enzymatic production in the liver. Yarrow is believed to help reduce pancreatic inflammation and improve blood circulation to the organ.